ocean vuong haters, I'm begging you to read a different book

a case for reading asian writers, not just asian americans

Only for my Substack subscribers (ily), here is an extended cut of this essay I was grateful to publish last month in one of my favorite magazines, the Emancipator!

I take pleasure in being a hater of fellow Asian Americans. We make it too easy! To be a first-generation Asian in America is to be caught in a perpetual state of puberty. There are growing pains and awkward phases, like obsessing over white romantic partners (see: the collective ouvre of Mindy Kaling), or appropriating Black culture (hello Awkwafina), or else writing so-called mango diaspora poetry romanticizing the homeland. (One could also go far-right, and join the ranks of billionaires, oligarchs, or Republican politics, but such Asian Americans are likely beyond saving.) It’s often very graceless. To be clear: I can afford to be a hater because I am in the second generation of queer South Asian American writers. (Each day I get on my knees and thank God for the brave Gen X and millennial writers who came before.) Despite the title of my own novel, I am not brave or unique or unprecedented, but I am lucky to have grown up with Asian American literature so plentiful that I can spend this essay telling you to read less of it.

Last month I read my way through the collective Asian American pandemonium over Ocean Vuong. The discourse was less about his new novel — which I am still on the library waitlist for, lol — but the space he carves for himself as an Asian American writer, which for some reason impacts what is possible for the rest of us. I was particularly taken by Song-Mai Nguyen’s argument that Vuong’s greatest crime is “blunt-force ethnic credibility” — falsely claiming to be a spokesperson of a culture he doesn’t really know, and ends up fetishizing for outsiders. Andrea Long Chu similarly critiques Vuong’s obsession with his white audiences: what does it mean when Asian Americans insist on writing from the margins, when in many ways, we are also at the center?

I empathize with Vuong’s diasporic melancholy. There is a real heartbreak among diasporic Americans, who feel their lives wrenched out of context by forces prior to their birth. There is a deep confusion, after this rupture, as to what comes next. In her novel Gold Diggers, Sanjena Sathian describes first-generation Indian Americans as “conceptual orphans.” “We had not grown up imbibing stories that implicitly conveyed answers to the basic questions of being,” her narrator explains. “What did it feel like to fall in love in America, to take oneself for granted in America?”

These are deep and worthy questions. And having a cohesive narrative of who you are is probably an essential component of psychological well-being. Indeed, ethnic American literature is preoccupied with finding belonging in America. An entire field of Asian American studies arose to map out a legible Asian American history, from Chinese exclusion to Japanese internment camps, staking a claim to American identity through its national past. These narratives can get sticky, particularly when they seek equivalence with other minority American narratives – think, for example, of the weird competitiveness between #StopAsianHate and the pre-existing #BlackLivesMatter movement – but it brings many Asian Americans comfort to insist that we’ve been part of America’s fabric all along.

To be fair, many Asian American writers are critical of the circumstances that made them Americans. “I am here,” Cathy Park Hong insists in her now-canonical memoir Minor Feelings, “because you vivisected my ancestral country in two.” Hong goes on to position her country, Korea, as “just one small example of the millions of lives and resources you have sucked from the Philippines, Cambodia, Honduras, Mexico, Iraq, Afghanistan, Nigeria, El Salvador, and many, many other nations through your forever wars and transnational capitalism that have mostly enriched shareholders in the States.”

Indeed, the danger of an Asian American artistic identity lies in the name: American. In the past years, as I’ve entered my twenties, I’ve found myself questioning this tendency to see America as an end in and of itself: “the third and final continent,” as Jhumpa Lahiri once described it. American identity becomes vexed for those of us who see the webs of oppression connecting our belonging and comfort here with the exploitation of others abroad. As a novelist I could (and admittedly do) wax poetic about my Asian parents’ struggles to build prosperous lives in America. But I must also contend with the fact that my parents’, and my, tax dollars are accordingly funding the genocide in Palestine, which is also in Asia. As the cracks in the American Dream reveal themselves, many diasporic Asians are looking for alternate ways to situate ourselves. It means “millions of people look[ing] at the West,” as Omar El-Akkad’s (life-changing) new memoir puts it, and saying, “I want nothing to do with this.”

“I came into political consciousness around Asian American causes, which were framed as an issue of anti-racism, access to the United States, and belonging to this country,” the writer Viet Thanh Nguyen told me in an interview for The Emancipator earlier this year. “Over the last couple of decades, I’ve [begun seeing] all those things as subsidiary to a greater cause of decolonization.”

Like Nguyen, my coming-of-age as an Asian American writer led me to think closely about decolonization. An important shift I made was choosing to read writers from the South Asian subcontinent, not just the diaspora. Not a South Asia “as written for its diaspora—the longing for an imagined homeland—or written for a colonial imaginary,” as the Indian writer Richa Kaul Padte explained, but a world that exists in conversation with ours, but also on its own terms. I try not to have rules, but if I did, I’d say that South Asian writers are usually more interesting, critical, and creative than South Asian American ones. Ladies, they’re running laps around us. Eating us up.

Reading South Asian women writers awakened me to the legacies of colonialism; of the interplay of systems of domination such as race and caste; of the potency of environmental movements in the Global South. As much value as I find in stories by “conceptual orphans” like Vuong – and I am guilty of being one of them – I encourage more diasporic readers to make a literary homecoming journey. I am begging us to leave Ocean Vuong and his ilk in peace and redirect our attention towards non-American books. When we do so, we are less likely to seek a “single story” of existence, to quote Adichie, or style ourselves as “voices for the voiceless.” The truth is that Western readers have enormous power as gatekeepers and champions of literature from our homelands, which are far from voiceless — it’s our job, and joy, to seek them out. A prize like the International Booker, or translation published in English, shifts the axis of attention, and enables more non-Western literature to become accessible to us.

This is a list of writers from India whom I recommend to readers seeking stories beyond the literary infrastructure of the West. This list is sort of arbitrarily limited to India but I am grateful for other recommendations. Many, but not all, of these books were originally written in regional languages and then translated into English, to challenge the stereotype that India’s only serious literature is written in English. This list is a starting point, non-exhaustive. The joy of reading, to me, is the rabbit hole of it, the exploration; the long game of telephone played between writers from different contexts, in the shared project of translating how it feels to be alive.

Heart Lamp by Banu Mushtaq

Mushtaq recently won the International Booker Prize for her collection of stories chronicling the lives of Muslim women and girls in South India. Heart Lamp, translated from Kannada, has been celebrated for its richly spoken language, humor, and attentiveness to interpersonal and community dynamics. Mushtaq, herself a lawyer and journalist fighting against religious and caste oppression, has faced death threats for her work. And yet she believes in the necessity of literature to amplify Muslim women’s struggles. “In a world that often tries to divide us, literature remains one of the last sacred spaces where we can live inside each other's minds, if only for a few pages," Mushtaq said in her Booker acceptance speech. (Shoutout also to Meghna Rao’s writing on on this book!)

The Weave of My Life by Urmila Pawar

This is my favorite book of all times and I wrote my undergraduate thesis on it. Pawar’s sweeping coming-of-age memoir, translated from Marathi, is an intergenerational portrait of Dalit women breaking cycles of trauma and an account of finding her voice as a writer and activist. Pawar is among the first generation of women from her community to have access to literacy, and she writes with an enormous sense of stakes as a result. Pawar’s commitment to community ethnography and attentiveness to the richness of women’s interior lives will resonate with readers of my other favorite writer, Zora Neale Hurston.

The Crooked Line by Ismat Chungtai

Ismat Chungtai, born in pre-Independence North India, chronicles the lives of Muslim women, power and freedom within the family, and the obliterating nature of desire. I first discovered Chungtai through her lesbian love story Lihaaf (The Quilt), considered pornographic upon its publication; The Crooked Line returns us to her world, a semi-autobiographical tale of a young Muslim woman coming of age with her nation. You already know I love a vaguely autofictional novel about a brown girl on her come up ;) Banger, babes. Trust me here.

When I Hit You by Meena Kandasamy

Kandasamy is an essential voice in contemporary Tamil feminist literature. When I Hit You is a portrait of the young writer’s escape from a physically abusive marriage to a Communist activist, and explores the misogyny underpinning even progressive spaces. Kandasamy cites a wide range of women’s narratives, from Hindu mythology to Ntozake Shange and Wislawa Szymborska and Sandra Cisneros, because she rightfully envisions this as a universal experience. Kandasamy writes and translates widely between Tamil and English; translating poetry, to her, has “no limit, no boundary, no specific style guide — you are free to experiment, you are free to find your own voice.”

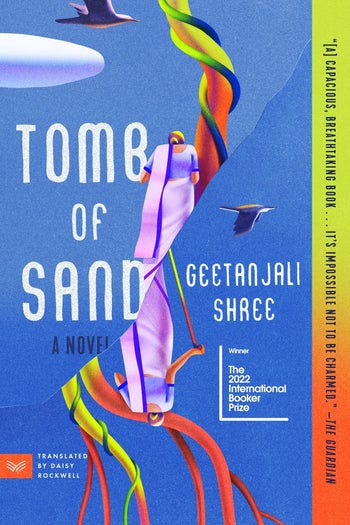

Tomb of Sand by Geetanjali Shree

Shree’s Hindi-language novel about an eighty-year-old woman who travels to Pakistan to face her unresolved Partition trauma, was the first Indian-language novel to win the Booker Prize, prior to Heart Lamp. Partition was a catastrophe in South Asian history, displacing upwards of 12 million people and leaving lasting wounds along religious lines that South Asians are still healing from, not even a century later. Despite its heavy subject matter, the Booker judges celebrated the novel as “enormously charming and funny and light.” I adored this novel as well for its portrayal of a transgender character, which I thought was very fun to read.

Quarterlife by Devika Rege

Rege’s coming-of-age portrait follows a group of young Indian millennials discovering themselves and their political identities against the rise of the Hindutva right-wing. It was originally published in India in 2023, and I probably would never have heard of it— but luckily for us, it was published for American audiences this year, I saw it on Merve Emre’s instagram, then gobbled it up. QUARTERLIFE is a hefty novel, which I always appreciate — Rege has a lot to say about this country that she loves and fears, and uses the wide toolkit of fiction at her disposal (an entire ensemble cast of characters!), culminating in an epic and terrifying climax of religious violence in Mumbai. The dark underbelly of national progress and change will resonate with American readers processing our nation’s own descent into xenophobia and fascism. Quarterlife is ambitious, a sweeping opus that tries to capture the churn of a nation in change, both critical and empathetic towards its privileged protagonists.

Ok that’s all for now! Thanks for reading <3

![Quarterlife [Book] Quarterlife [Book]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!CHS1!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F4b73fae2-8666-4d00-851e-8383021559b6_1712x2560.jpeg)

Loved the thesis of this piece. Americans don’t read enough books from authors outside the states. To me the purpose of reading literature is to get outside your worldview, open your eyes, be uncomfortable and “travel” intellectually. To read something that’s not necessarily relatable to you. I’ll look into these recommendations. Every time I read literature written by someone born and raised in a different country from my own I always feel like I learned beyond.

I read a good amount of Japanese literature. If you're in a bookstore looking for good, recent literary fiction, a good strategy is to look for Japanese author names. They take the craft seriously, and it's an artistically conservative culture, so the stories usually lack the kind of didactic left-wing politics that have invaded American literary fiction.